Why are some Alveopora corals bleaching in Siquijor?

- Laura

- Sep 21, 2025

- 4 min read

These days, all around the Philippines, our coastal waters are hot, more polluted, and often clouded by excess sediment from coastal activities. Coral colonies feel these changes and these fragile organisms stressed with cascading impacts on the reef.

In Siquijor Island, we are generally blessed with high coral cover and favorable conditions for them. Yet, as it is the case everywhere, pressures on marine ecosystems are intensifying as population and tourism grow ( followed by coastal development), alongside the looming impacts of overfishing and climate change directly threatening our reefs.

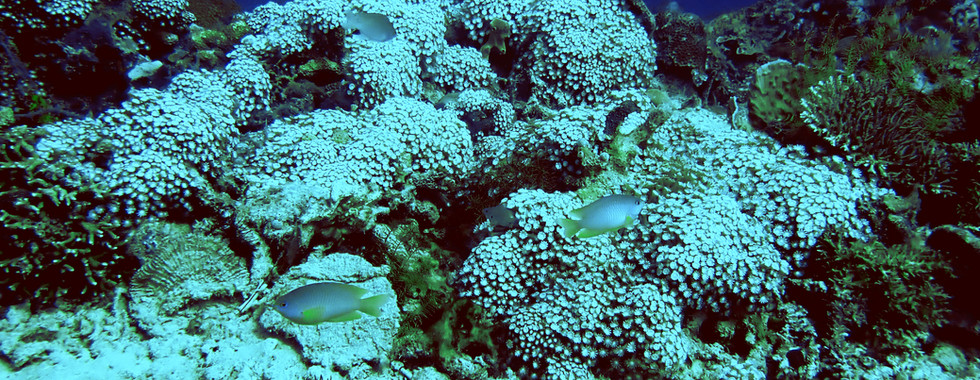

Yesterday, during one of our dives with the team, we were saddened to witness an entire section of bleached coral colonies in one of our nearby reef. Passed the urge to cry, we noted the location, depth, and observed a bit closer the affected corals. We were at approximately 17meter, in a site with clouded visibility, all impacted corals were from the Alveopora genera while neighboring corals did not show any visible signs of stress. As this is not the first time we noticed Alveopora bleaching on deeper reef sections this made us wonder. Are Alveopora less thermally resilient than other corals? Or are they more affected by turbidity, pollution, or other stressors?

Curious? We looked it up, and are happy to present some interesting insights on the matter.

Step 1, we looked into the data.

A quick review of CRCP's ecological monitoring dataset on reef health over the past two years reveals interesting patterns. While coral bleaching has been relatively low in Siquijor, the top five most vulnerable genera were:

Of our monitored bleached corals, 8% were Alveopora, only surpassed by Goniopora at 17%. This is notable considering their low abundance on our reefs — Alveopora represents just 0.3% of hard coral cover, and Goniopora 2.5%.

Step 2, What does the literature says?

Studies on thermal resilience comparisons of corals are limited and almost none covers Alveropora aside from some bleaching events reports. However some explanations may still be found in studying their ecological niche and growth strategy.

Although Alveopora (Acroporidae) and Goniopora (Poritidae) belong to different families — based on skeletal morphology and molecular phylogenetics — they share many ecological functions and habitat preferences. These similarities helped us understand their stress thresholds.

Looking for insights about corals, looking into Corals of the World, and the work of Veron is always a great way to start and is always guaranteed to teach you something. In there, we could read that Alveopora form massive or branching colonies, often irregular in shape. Their skeleton is light, consisting of interconnecting rods and spines. Corallites have lattice-like walls, with fine spines sometimes connecting to form a columella tangle. Polyps are large and fleshy, normally extended day and night, with 12 tentacles often ending in knob-like tips. Similar genus: Goniopora have 24 tentacles and much greater skeletal development.

Veron notes:

“It is rare to see many Alveopora species together in the same place, as habitats of individual species are very different… These habitats include protected turbid environments (the majority of species), exposed upper reef slopes (e.g., A. marionensis), and rocky foreshores of subtropical locations (e.g., A. japonica).”

Indeed, many species of Alveopora — such as A. gigas, A. catalai, or A. tizardi — prefer moderately turbid water or deeper reef zones. Fast-growing, light-hungry corals like Acropora or Pocillopora dominate shallow, clear habitats. By contrast, Alveopora avoids competition by colonizing less popular, shaded areas.

While still reliant on light to sustain their symbionts, Alveopora’s large, fleshy polyps allow them to feed efficiently on plankton and suspended particles, making them more efficient at heterotrophy than many corals. Despite reduced light, turbid water, rich in suspended organic matter, allows them to easily supplement photosynthesis and provides a nutritional advantage. Their fleshy tissue and large polyp expansion also allow them to actively clear sediments using mucus and ciliary action and persist where thin-tissued corals might be smothered.

Interestingly, Goniopora corals show a similar adaptation, thriving in turbid or deeper environments and opting for similar strategy.

Why do they bleach first?

Turbid habitats protect Alveopora from competition and provide abundant food. However, these low light environments also limit photosynthetic energy, meaning the corals live closer to their energetic threshold. When thermal stress occurs, they bleach faster than thicker-tissued corals because they cannot compensate enough.

Recovery potential

However, while these findings seem gloomy for Alveopora corals and surely places them amongst vulnerable corals in a climate crisis setting, the situation is not entirely bleak.

Their efficiency in heterotrophy plays a key role. During or after bleaching, they can capture plankton and suspended organic particles to replenish energy, which may help faster recovery as long as water quality is good and plankton is available and abundant. As long as heterotrophic feeding can compensate, colonies can survive bleaching episodes that would kill strictly autotrophic corals.

Repeated or prolonged stress, however, will reduce resilience over time, limiting recovery and reproduction.

Key takeaways

Most Alveopora species are highly adapted to turbid, deeper, or shaded habitats.

Their large polyps and heterotrophic feeding help them persist where other corals cannot.

They bleach quickly because turbid environments reduce baseline photosynthetic energy.

Recovery is possible, provided water quality and plankton availability are sufficient, but repeated stress diminishes resilience.

Understanding these ecological traits helps us anticipate how sensitive corals respond to climate change and local stressors — a crucial step in managing and protecting local reefs. It is also fascinating to know that response to thermal stress among corals species have been proven to be deeply impacted by local environment making it difficult to establish global rules and guidelines but just as exciting to study how corals thrive in different ecosystems and draw patterns.

Interesting studies to read:

Comparing bleaching and mortality responses of hard corals between southern Kenya and the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, Mcclanahan, Marshall, Toscano, 2004

Consequences of Coral Bleaching for Sessile Reef Organisms, Mcclanahan, Weil, Baird, Cortés, 2008

Predictability of coral bleaching from synoptic satellite and in situ temperature observations, Mcclanahan, Ateweberhan, 2007

Energetics approach to predicting mortality risk from environmental stress: a case study of coral bleaching, Anthony, Hoogenboom, Maynard, Grottoli, Middlebrook, 2009,

Heterotrophy in Tropical Scleractinian Corals, Houlbreque, Ferrier-Pages, 2008

Turbid reefs moderate coral bleaching under climate‐related temperature stress

Sully, van Woesik, 2020

Alveopora japonica Conquering Temperate Reefs despite Massive Coral Bleaching, Kim, 2022

Comments